Handout – Chapter 8 – Key Principles of Effective Challenging (PDF)

The word ‘challenging’ in its everyday use can imply an aggressive, battling stance. In the therapy context, however, challenging comes in many guises ranging from robust provocative confrontation at one end of the spectrum to tender, compassionate, evocative challenge. Challenges can be subtle and tacit – just receiving the therapist’s silent, loving gaze can be a massive challenge for some.

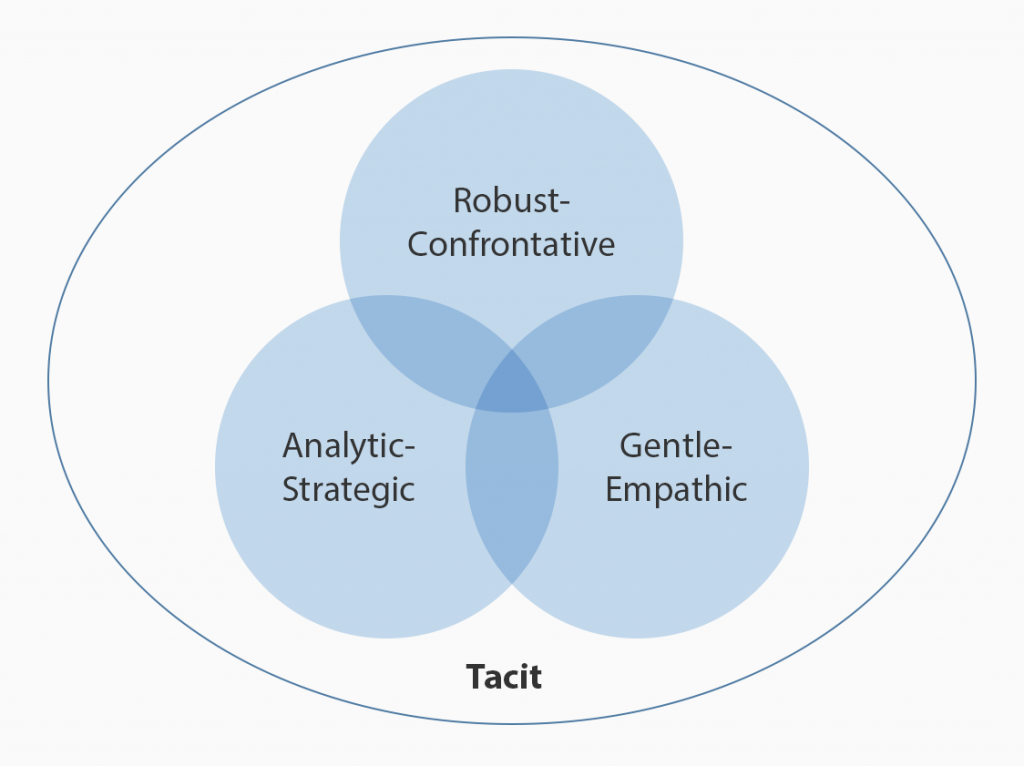

Four general styles of challenge are considered here, what I’m calling: robust-confrontative; analytic-strategic; gentle-empathic; and tacit (see figure 1).

Robust-confrontative challenging

Robust-confrontative challenges are provocative and forceful, and involve open disagreement and/or a setting of a firm limit or boundary. These challenges tend to be employed when dysfunctional, problematic, self-damaging, or unethical behaviour requires direct confrontation.

Yet even when this type of challenge is delivered in a strong way, it still is compassionately done in a relational context which aims to ensure the client has room to make their own choices, e.g.:

Therapist: “I really want to hear what you’re saying but I’m finding it hard to concentrate. You’re speaking very fast. What’s happening for you?”

or

Therapist: “You said earlier that you wanted to talk about the conflict with your boss. But we’ve just spent the last fifteen minutes talking about your friend. Are you maybe avoiding something here?”

In some situations, however, more muscular confrontation may be required, as in this intervention by a therapist working in an adolescent unit for ‘troubled teens’:

Therapist: “What the hell are you doing, Cassie?!? Look at yourself and the choices you’re making! You’re sleeping around, having unprotected sex. Why?! What are you getting? If its love you’re wanting you’re looking in the wrong place. You’re just a trophy f*** for those boys.”

Early gestalt therapy was characterised by this kind of robust intervention. Check out Perls’ approach in his infamous interview with ‘Gloria’ where he accuses her of being a “phoney”. He provokes her to be angry to cut through her smiling deflection.

A strong, boundaried therapeutic presence and realistic but firm confrontation is probably the intervention of choice in the early ‘testing and resistance’ phase of working with ‘borderline’ clients. However, in the case of clients more inclined towards narcissistic and schizoid styles, confrontative interventions are likely to be too shaming and intrusive. The therapist needs to work more analytically or empathically, making use of the other forms of challenge. Challenge here is ideally negotiated and perhaps even asked for.

Analytic-strategic challenging

Analytic-strategic challenging is engaged when therapists work more cognitively or aim to give honest feedback or when inviting the client to take responsibility for their life choices.

Working cognitively, the therapist might aim to encourage clients to be aware of their self-protective responses (‘creative adjustments’ in gestalt language), perhaps suggesting how reasonable they were in the circumstances. The challenge would then come with an invitation to perhaps do something different(?)

Challenges can also be delivered as part of giving feedback regarding the client’s behaviours (rather than interpreting internal processes). Rather than saying, “I think you’re angry with me”, it might be more effective to offer feedback: “I’m noticing your clenched your fists. What might they be saying?”

When inviting a client to take responsibility for choices, a therapist might say, “You’re at an important choice point. Do you want to carry on feeling stuck and lonely or might you feel ready to do something different?”

Gentle-empathic challenging

Gentle-empathic challenging involves attuning to and verbalising feelings. At the same time a challenge is issued, one which calls attention to something that doesn’t quite fit or tries to bring something new into the client’s awareness. For instance:

- Client: (deflecting) “It’s not a big deal.”

Therapist: “It’s a HUGE deal! This is important!” - Client: “I always mess up.”

Therapist: “Always?” - Therapist: “You say you hate your father and I hear some of your rage. But I also hear how you respect him and care for him. Perhaps there is a little love there too?”

Tacit challenging

Tacit challenges are the more ever-present silent ones which arise as part and parcel of the therapeutic encounter. Its worth remembering that it is often challenging simply to be in therapy! For some clients, just sitting in the therapy room can be a challenge. Clients can also often find it hard to be in the presence of a loving, supportive, compassionate therapist. The potential power and nourishment of the therapeutic relationship can itself be hard to take. How challenging might it be for a client full of self-critical shame to be looked at with kind, affirming eyes?

Reflections

Challenge is both a necessary and ever-present component of therapeutic process. The different styles in which therapeutic challenging can be issued – be it vigorous-confrontative, analytic-strategic, gentle-empathic and tacit – aim to promote self-awareness (e.g. of the blind spots which keep clients stuck in self-restricting, self-damaging ways).

We tailor our approach to each individual, finding the tricky balance between challenge and support. The art of our relational integrative practice occurs as we negotiate the tensions of safety and risk; pushing and accepting; imposing and allowing; appreciating and disagreeing… We intuitively sense when to push and when to ease off recognising that what is a huge challenge for one person may be ‘water off a duck’s back’ for another. The key is to offer the challenge in an empathically attuned being-with way given the particular relational context.

I like the metaphor that gestaltist Philippson (2012) uses that, in the face of a closed door, you can ‘wait’, ‘knock’ or ‘push’ on it. The decision to challenge is made on the basis of how much (self and external) support both client and therapist have. Phillippson recommends waiting if the client is terrified and knocking to check how someone is doing. The more confrontative pushing of the door is best when limits need to be set and/or when the transference would be too destructive if the therapist waited.

Of course, we don’t always get it ‘right’. Many of us avoid challenging and its easier to be nice and empathic. And, if we’re struggling to give the challenge ourselves, our tensions may get communicated resulting in an unconvincing or unduly abrasive intervention. But it is a skill we can learn and it gets easier with practice. First, we need to believe in the point and power of offering challenge.

Resources

Yontef offers detailed advice and useful case illustrations as he explores our work with individuals with borderline versus narcissistic adaptations (see: Yontef, G. M. (1993). Awareness, Dialogue, and Process: Essays in Gestalt Therapy. Highland, NY: the Gestalt Journal Press.)

Yontef offers detailed advice and useful case illustrations as he explores our work with individuals with borderline versus narcissistic adaptations (see: Yontef, G. M. (1993). Awareness, Dialogue, and Process: Essays in Gestalt Therapy. Highland, NY: the Gestalt Journal Press.)

See: Egan, G. (2010). The Skilled Helper: A problem Management and Opportunity Development Approach to Helping (9th Edition). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole – especially chapter 8, which offers numerous examples of effective challenging. Egan lists the targets of challenge as:

See: Egan, G. (2010). The Skilled Helper: A problem Management and Opportunity Development Approach to Helping (9th Edition). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole – especially chapter 8, which offers numerous examples of effective challenging. Egan lists the targets of challenge as:

- Self-defeating mindsets

- Self-limiting internal behaviour

- Self-defeating expression of feelings and emotions

- Dysfunctional external behaviour

- Distorted understandings of the world

- Discrepancies in thinking and acting

- Unused strengths and resources

- The predictable dishonesties of everyday life