Handout – Chapter 4 – Kohut Theory (PDF)

Handout – Handout of core relational elements

Empathy and attunement underpins therapy. When we empathically attune to another we gently tune into, sense, and resonate with their experience. Think of two violins in a room: It can be amazing to see how when the strings on one are plucked, the other vibrates too when it’s tuned to the same frequency (Rowan & Jacobs, 2002).

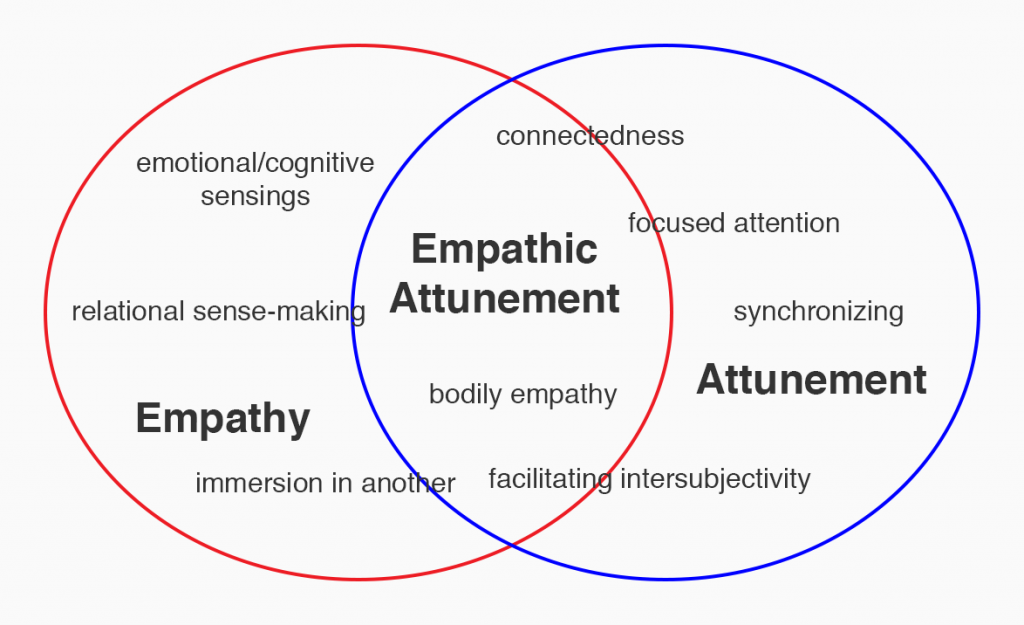

Although there is a great deal of evidence that shows how empathy and attunement are among the most demonstrably effective elements of the therapeutic relationship (Cooper, 2008), they are elusive processes and hard to describe. Different theorists define them in different ways: some use the terms interchangeably, others sharply separate them. In general, person-centred therapists are particularly concerned with ’empathy’ while relational psychoanalytic therapists favour a focus on ‘attunement’.

My approach is to visualise the two concepts as separate but overlapping circles, with the overlap representing ’empathic attunement’ (see figure 1).

Empathy

The term ’empathy’ (from the German Einfühlung) means gently sensing another person in order to better appreciate their experience. It’s about ‘stepping in another’s shoes’. Carl Rogers (1980, p.142) described it as being sensitive to “felt meanings which flow in the other person”.

Fundamentally, empathy is an embodied relational process. When clients come to therapy, they can struggle to express their experience and it’s the therapist’s role to sense more and check out their meanings. “Behind your words I’m hearing you say you’ve lost hope. Am I picking that up right?” Or “That’s some burden you’ve been carrying. I’m guessing you feel robbed?”

In moments of relational depth (Mearns & Cooper, 2005), we empathically attune to the whole of the client’s being (resonating with them) and we tune into the ways they are different from us. We don’t simply say, “I know your experience of raging against your mother because I experience the same”. It’s also not about fusing with the client (excessive confluence) nor projection of our own perspective. Empathy requires a shift in perspective.

When deep empathy is engaged it is akin to a kind of receiving which is an embodied lived experience of itself. When I am with a client, I am over ‘there’ with them, sensing, moving, empathising, responding and resonating with my whole body-self.

At the same time, we need to be sufficiently self-aware to hold on to our own presence and identity. It’s not about becoming the other. For instance, I will try to be aware of my own bodily sensations like having a clenched, tight ball in my abdomen. Is that me? Or does it belong to my client? Might my sensation be linked in some mysterious way to the client’s experience? Could it be that my body is vibrating to something occurring between? In this mode of embodied empathy, Cooper (2001, p.223) explains, the therapist is “not resonating with specific thoughts, emotions or bodily sensations, but with the complex, gestalt-like mosaic of her client’s embodied being, that initial primal thrust of the client’s experiencing as it emerges into the world.”

Attunement

Applied to therapy, attunement is the term used to describe our reactiveness to and fit with clients. The process is similar to the way an attuned parent, noticing a child’s distress, will take steps to offer comfort. It’s about giving appropriate responses, not just crying because the client is crying.

It’s common to hear relational psychoanalytic commentators focus more on attunement rather than empathy. When we attune to a client we are brought into harmony with them; we adjust to them in sympathetic, synchronous relationship. Other musical metaphors like resonance, rhythm, duet and chorus come to mind too (perhaps this is unsurprisingly given the ‘tune’ in at-tune).

Attunement is seen as the “performance of behaviors that express the quality of feeling of a shared affect state without imitating the exact behavioral expression of the inner state” (Stern, 1985, p.142). Successful attunement is seen in the way a mother mirrors and enables as she joins with her baby. She matches her child, for example, when the infant is expressing joy, distress or need. In addition, attachment theory suggests that the capacity to reflect on one’s emotional experience and on the mind of the other (called ‘mentalising’) grow through caregiver’s sensitive attunement (Fonagy & Bateman, 2006).

‘Empathic attunement’

While empathy and attunement can be contrasted, they also overlap. The concept of empathic attunement holds both concepts together. For instance, Greenberg, Rice and Elliot (1993, p.104) provide a definition of attunement which implicitly embraces empathy:

In empathic attunement, one tries to respond to the client’s perception of reality at that moment, as opposed to one’s own or some ‘objective’ or external view of what is real… The therapist takes in and tastes the client’s intentions, feelings, and perceptions, developing a feel of what it is like to be the client at that moment. At the same time, he or she retains a sense of self, as opposed to being swamped by or ‘fusing’ with the client’s experience.

Erskine, Moursund and Trautmann (1999) make a similar argument: Effective therapy depends on attunement, with empathy as the foundation. For them, ‘inquiry, attunement and involvement’ are dimensions of an overall empathic frame within which the client’s growth is nurtured. It’s about kinesthetically sensing and moving with the client in a contact-enhancing way.

They offer a comprehensive description of how the multi-layered ways in which therapists use this empathic attunement, as including:

- Affective attunement – Here the therapist responds at three levels: noticing the client’s affect; vicariously feeling to the emotion; and communicating a response.

- Cognitive attunement – With this, the therapist attempts to understand the client’s perspective, thinking and meanings.

- Developmental attunement – The therapist engaged at this level thinks developmentally and tries to attend to a client’s ‘Child’s’ needs, particularly when they are in more regressed states.

- Rhythmic attunement – Here the therapist is responsive to the client’s own habitual way of being and rhythmic patterns. For example, if the client is a slow thinking, then the therapist will adapt and similarly go more slowly; if a client is quite regressed, the therapist will speak more simply.

See the attached handout on Kohut’s self-psychology theory and implications for empathic attunement.

Reflections

Rather than getting caught up in the semantic intellectual debate about whether something is empathy or attunement, the concept of ’empathic attunement’ works for me. Whatever we call ‘it’, the important point is that, as therapists, we need to allow ourselves to be responsively open to the other.

Of course we inevitably move in, out and through different intensities of closeness and distance. It is not uncommon to feel a little distant and not well tuned in at one moment and then suddenly the distance can dissolve as we open to the client or perhaps following the discovery of some shared experience. We can also find ourselves pulled into confluence (positive or negative) and an identification so intense it can feel like we’re merging with the client.

To empathically attune at a deep (perhaps embodied) level, we are called on to let ourselves go into the process; to release our own Being in order to Be-with in the moment. At this point we are open to the other and to being touched by them. It’s about letting embodied feelings, thoughts, impressions and intuitions appear – letting go of knowing certainty to see what emerges. It means welcoming whatever becomes figural in the moment. But this is a process of embodied intertwining, is not a merging: we need also to hold on to ourselves. This respects the otherness of the Other.

Tuning in to the Other and to me, I also tune in to the between. It is as if I am listening intently and with all of me for a tune that is all of us (me, other and us). I listen to the tune being sung by the Other. I try and connect with the deeper song – the song of contact, meeting, connectedness, longing. Even when hidden beneath the negative or closed and cut off, I strain gently to listen to the quiet hum of faith buried beneath the weight of the life of the Other. The weight that I also know and have known – that we all know – of joy and sorrow and hope and despair…It feels like being grounded in a repose of lightness that is yet full and deep and open and present with myself and the Other in a spirit of acceptance and compassion.

(Finlay & Evans, 2009, p.125).

Resources

Erskine et al’s book (Erskine, R.G., Moursund, J.P. and Trautmann, R.L.(1999). Beyond Empathy: A Therapy of Contact-in-Relationship. London: Taylor & Francis) is a wonderful, broad-based resource concerned with empathy and attunement and includes much on practical relational implications.

Erskine et al’s book (Erskine, R.G., Moursund, J.P. and Trautmann, R.L.(1999). Beyond Empathy: A Therapy of Contact-in-Relationship. London: Taylor & Francis) is a wonderful, broad-based resource concerned with empathy and attunement and includes much on practical relational implications.

Numerous online YouTube resources show instructive mother-baby interactions: for example

Also check out the many videos available which show how babies are naturally predisposed to attuning to others in relationship: for example, this one demonstrating in lively fashion the mirroring that occurs with (and between) twins:

For a comprehensive account of the neurobiology underlying attunement, and attachment and trauma, see Allan Schore’s (2001) account on: http://www.trauma-pages.com/a/schore-2001a.php.